By Rishikeesh Wijaya*

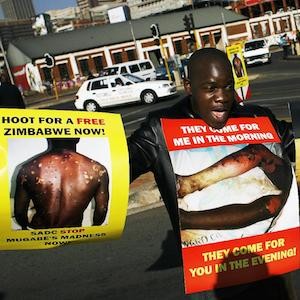

Uproar about purported ‘abuses’ of diplomatic immunity has not been uncommon, most recently involving the wife of the sitting Head of State of Zimbabwe, Dr. Grace Mugabe. Media reports assert that Dr. Mugabe attacked a South African model with a piece of electrical cord in a Johannesburg hotel suite. South Africa retrospectively granted her diplomatic immunity, following an assertion by the Embassy of Zimbabwe, and she eventually left the country to return to Zimbabwe with no charges pressed against her.

Uproar about purported ‘abuses’ of diplomatic immunity has not been uncommon, most recently involving the wife of the sitting Head of State of Zimbabwe, Dr. Grace Mugabe. Media reports assert that Dr. Mugabe attacked a South African model with a piece of electrical cord in a Johannesburg hotel suite. South Africa retrospectively granted her diplomatic immunity, following an assertion by the Embassy of Zimbabwe, and she eventually left the country to return to Zimbabwe with no charges pressed against her.

This was a “U-turn” from the initial decision preventing her from leaving pending the outcome of investigations. Deputy President of South Africa, Mr. Cyril Ramaphosa in response to questioning by South African Members of Parliament, said that immunity was granted in line with “internationally-recognised immunity regulations” but also admitted that it was “the first time [they] have utilized this type of convention”. It is unclear what convention he was referring to.

A separate incident occurred during Turkish President Erdogan’s trip to the United States America in May 2017. Members of his security detail and security guards from the Turkish embassy clashed with peaceful protestors outside the home of the Turkish ambassador in Washington DC.

Diplomatic immunity was initially claimed by Turkish authorities but it has now been reported that 19 people, including 15 identified as Turkish security officials were indicted by a grand jury in Washington DC. Several of these security officials returned to Turkey and it is unclear if there will be any legal repercussions in the United States. It is also unclear if any of those indicted remain in the US as diplomatic staff for Turkey. Continue reading

South Africa has formally begun the process of withdrawing from the International Criminal Court (ICC).

South Africa has formally begun the process of withdrawing from the International Criminal Court (ICC).