by Sander Wirken

Former Guatemalan national police chief Sperisen sentenced to life in Switzerland

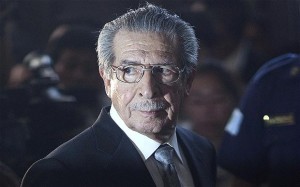

An accused standing trial for the murder of ten people is not a common occurrence in Swiss criminal courts. Erwin Sperisen, a former Guatemalan police chief (2004-2007) and dual Guatemalan-Swiss national, stood trial for just that this year. On 6 June 2014, he was sentenced to life imprisonment for the extrajudicial execution of seven prisoners in a campaign of ‘social cleansing’ directed by the national police leadership. The ruling marks an important victory for justice and signals that fleeing to another country is no longer a guarantee of impunity for Guatemalan criminals.

During the Oscar Berger government (2004-2008), a parallel structure emerged in Guatemala within the Ministry of the Interior and the National Civilian Police, led by the police top leadership and the Minister of the Interior. Amongst other activities, the structure dedicated itself to ‘social cleansing’, i.e., ridding Guatemalan society of what those involved in that process regarded as ‘undesired elements’.

The charges against Sperisen revolved around two incidents. First there was the case of three inmates that had escaped from the El Infiernito prison in October 2005. The escapees allegedly resisted their arrest and died in an armed confrontation with police officers. The bullet impacts, witness testimonies and other evidence were inconsistent with that scenario however and pointed rather at the escapees having been executed, after which the crime scene had been altered to resemble an armed confrontation. The Swiss court was convinced that the three escapees had indeed been extra-judicially executed. However, the court was not convinced beyond any reasonable doubt of Sperisen’s personal involvement in the killings, as Sperisen had not been present at the scene of the crime and no clear evidence linking him to the material authors of the executions was provided.

The second incident related to the operation of the Guatemalan police to reestablish control over the Pavón prison in September 2006. When control over the prison had been reestablished and prosecutors and the media were allowed inside, seven inmates were dead. The Guatemalan police claimed that the inmates had violently resisted the police and had died in an armed confrontation. Again, like in the El Infiernito case, the crime scene was evidently altered however, and the nature of the bullet impacts and other indicators pointed at close-range executions rather than an armed confrontation. The bodies had been moved post-mortem and guns had been placed in the hands of the dead inmates. One of the dead inmates, allegedly killed during an armed confrontation, even had a gun in his hand that was missing its hammer and could hence never have served to shoot a single bullet.

Sperisen had been present during the Pavón operation at the key places, during the key moments (» l’intéressé se trouvait aux endroits-clés, aux moment-clés ») according to the Geneva tribunal. Not only had he acted as the commander of his police officers during the operation, he had himself also actively participated in at least one of the executions. Sperisen was found guilty of personally carrying out the execution of one of the victims and of being co-author to the execution of the six other inmates. Given the seriousness of the facts, the number of victims and the total absence of empathy on the part of Sperisen, according to the Swiss court, life imprisonment was the only appropriate punishment. (» Compte tenu notamment de la gravité des faits, du nombre de victimes, de l’absence d’empathie à l’égard de celles-ci et de l’absence de prise de conscience de la gravité de ses agissements, seule une peine privative de liberté à vie est susceptible de sanctionner le comportement de prévenu. «)

Narrowing the impunity gap

Impunity used to be the rule for powerful Guatemalan criminals. Things are changing however, in great part thanks to the UN-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). Former president Ríos Montt (1982-1983) was convicted to 80 years imprisonment for genocide and war crimes by a Guatemalan trial court last year. Whilst the Constitutional Court subsequently annulled his conviction, the fact that Ríos Montt was made to stand before a court of law marked an unprecedented shift and breakthrough for justice. Former president Portillo (2000-2004) was also brought to trial. He was acquitted but was then extradited to the United States on money laundering charges and convicted there.

The parallel state structure to which Sperisen had belonged was thoroughly investigated by CICIG. Many of its key players were brought to justice. Third in command of the police at the time, Soto Diéguez, was convicted in Guatemala and sentenced to 33 years imprisonment. Three key members of that parallel system fled to Europe but were soon located and brought to justice. The case in Austria against the then number two of the police, Figueroa, ended in an acquittal. Sperisen was found and prosecuted in Switzerland. Former Minister of the Interior, Carlos Vielman, is awaiting trial in Spain.

The Guatemalan justice sector is thus slowly improving and other countries are helping closing the impunity gap that has affected Guatemalan society for so long. The quashing of the genocide conviction and acquittal of former President Portillo might suggest that fighting crime and impunity remains a demanding task. The recent ousting of the brave Attorney General Claudia Paz y Paz is also a cause for great concern for the future of Guatemala’s justice sector and for its independence. But the wheels of justice are moving, once untouchable individuals are now brought to justice and judicial and prosecutorial authorities are increasingly finding the courage to investigate their crimes.

The efforts of the United States, Switzerland, Austria and Spain to investigate and prosecute Guatemala’s most powerful criminals who seek refuge in their territories are crucial to the fight against impunity and further the internal process of change within Guatemala. The Sperisen judgment in Switzerland led to a wide public debate in Guatemala about the nature of his crimes and about the state of Guatemala’s justice system. Should the Guatemalan prosecutorial and judicial system continue to improve, accountability should become the norm and impunity routes for perpetrators of atrocities will become ever narrower. Foreign states can help that process by denying criminals a safe harbor in which to hide.