by Thierry Cruvellier*

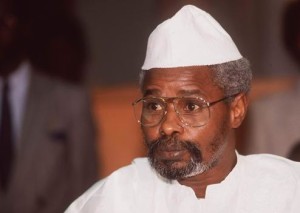

DAKAR, Senegal — Surrounded by 10 muscular prison guards, Hissène Habré, his frail body entirely swathed in white, looked smothered in his chair. He was sitting in the front row of the immense courtroom, fingering Muslim prayer beads. His boubou covered all but his eyes, and they were partly hidden by his glasses.

Mr. Habré, the 72-year-old former president of Chad, is accused of crimes against humanity, war crimes and torture regarding the deaths of an alleged 40,000 people during his rule between 1982 and 1990. July 20 was the first day of his trial before the Extraordinary African Chambers, a special court he has repeatedly denounced as “illegitimate and illegal.” And almost as soon as it started, it stopped: Mr. Habré, and his lawyers, refused to participate, and on the next day the proceedings were suspended.

The Habré trial is the event of the year in the field of international criminal law. With tensions growing between the African Union and the International Criminal Court — which African states accuse of being biased against them because it prosecutes mostly crimes committed in Africa — the E.A.C. was being touted, at least by Senegal’s justice minister, as the advent of an “Africa that judges Africa.”

Hissène Habré after a court hearing in Dakar in June. Credit Seyllou/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

But on the first day of what may be the court’s only trial, Mr. Habré derided the E.A.C., or C.A.E. in French, as the “Comité administratif extraordinaire,” the Extraordinary Administrative Committee. He called the judges — two from Senegal, one from Burkina Faso — “simple functionaries tasked with carrying out a political mission.” As the hearing was about to begin, Mr. Habré stood up and shouted, “Down with imperialism! Down with traitors! Allahu Akbar!” A dozen of his partisans rose from their seats nearby and chanted: “Long live Chad!” “Long live Habré!” “Mr. President, we are with you!” Continue reading